About Me

I was born and raised in Lentegeur, Mitchells Plain, a predominantly Coloured township located approximately 30 kilometers from Cape Town’s Central Business District. Mitchells Plain was developed in the early 1970s as part of the apartheid government’s forced removals strategy, designed to (re)settle Black and Coloured families who had been displaced from areas such as Newlands, Rondebosch, Sea Point, and District Six under the Group Areas Act of 1950. This Act was one of several legislative instruments that institutionalised racial segregation and so-called ‘separate development’ following the National Party’s rise to power in 1948.

From an early age, I became acutely aware of how people were classified according to race and other socially constructed markers of difference, and how these classifications profoundly shaped life opportunities and trajectories. The lived experience of navigating racialised inequality on the Cape Flats remains a deeply formative part of my identity and continues to inform and inspire my teaching, research, writing, and activist engagements.

The Formative Years: My Experience of Schooling and Proximity to Trouble

I attended Merrydale Primary, then progressed to Portland Senior Secondary School. I remember enjoying primary school very much, except for the obvious routine beatings I would get from my teachers for initiating a joke, whistling in class, throwing paper balls at my peers, and walking around when the teacher had to leave the classroom. At primary school, I was indeed a troublemaker. I visited the principal’s office regularly, almost weekly. All my teachers spoke of me as the “troubled” boy. Indeed, I got in trouble often and created much trouble for my peers. My mother had to come to school so regularly, she decided to become a permanent volunteer at the school, so that if I caused trouble, she would always be on hand.

I am sure there were many moments that I was my mother’s worst nightmare, but one thing remained for sure: I knew she had my back. In hindsight, I think its my troublesome behaviour at primary school that fostered our eternal bond and my undying appreciation for her love and guidance, even in her death. Due to my troublesome behaviour, I did not have many friends: parents would forbid their children to play with me. To make matters worse, I was the ‘laat lammertjie’[1] and too young to play with my siblings as they were all 10 years and older than me. My mother became my best friend, and despite the trouble and, I’m sure, embarrassment I caused, she always encouraged me to work hard, be diligent, and make a success of my education. I heeded her advice, and my trajectory changed over the next few years.

From grade five until grade eight, I was a top achiever. Annually, I would receive sports, academic, and leadership awards. In my final primary school year, I received the award for the ‘most outstanding learner’. At high school, when I arrived in grade nine, I was selected as class prefect and elected to serve on the learner representative council, both positions I occupied until I matriculated. In grade eleven, I was elected as deputy president of the LRC and chairperson of the Christian student fellowship. In my matric year (grade twelve), I was head-boy and President of the LRC and served on the school governing body and various other committees. Throughout my high school career, I was consistently at the top of the school’s best academic achievers. But there is more to this story.

Despite my rather showy academic credentials, I was somehow unable to shake off the trouble. Trouble followed me, albeit in different ways. For example, at primary school, teachers would often ask me to be a class monitor when they had to leave the class, instructing me to report any transgression. My reporting of such transgressions isolated me from male peers and frequently led to after-school fights. I remember one windy afternoon on my way home from school, I had to face about 7 or 9 boys waiting for me outside the school gates. A fight ensued and turned ugly very quickly. I was left with a broken arm, bulging lips, a broken nose, and swollen blue eyes. Since that day, my mother swore to only purchase blue school shirts, her reason being so that I would be easily identifiable in case I had to endure such an experience again.

At high school, too, despite my impressive academic achievements, I was often referred to as the troublemaker (some teachers called me a ‘fighter lighter’). I loved jokes and humour. I still do. I collected Chappies bubble-gum wrappers for its jokes and the ‘did you knows’, I also listened to Tolla van der Merwe and Leon Schuster, two very popular Afrikaans storytellers and pranksters. I also asked my classmates to look for jokes and pranks that we could share and perform on our peers and teachers. Strange concepts in biology, particularly those related to the sexual organs and/or procreation, provided for hours worth of giggles, sounds, and drawings we would send around in class. My strategy was to always initiate (hence my nickname “fire lighter”) and let others catch the flame, and they gladly obliged, time after time. Getting my peers into trouble, I confess, was my greatest prank of all.

My sense of humour, coupled with my academic standing, afforded me much popularity with the ‘sporty’ and the ‘gangster’ boys as well as ‘pretty’ English-speaking girls, in the same way that I was popular with the other nerds and ‘lose girls’. Additionally, teachers idolised me…well, not everybody (especially not the victims of my pranks), but most did. On the odd occasion that I was caught pranking or making a funny sound in class, teachers would send me to the principal’s office. Unlike other boys who would be suspended or sent home for disturbing the class, the principal would simply instruct me by saying: ‘Trevor, please go back to your class and stop fooling around!’. This created some serious trouble for me with other boys who were severely punished for similar offences. Thankfully, I negotiated my way out of this conundrum with my peers by offering to help with their homework and ignoring future transgressions such as smoking on school premises and coming late.

Ironically, despite my jokes and troublemaking tendencies, I was very involved in church related activities, and loved singing. I was a youth leader and sang in the worship team (the band and singers) of my then church. I also headed the youth music and arts department and frequently performed various religious songs in church and at conferences, as well as led the worship team (the band and singers) at various youth events. My love for singing spilled over into the school arena. This was a big moment for me in terms of grappling with “what kind of boy/ young men I was going to be”. Indeed, I was confronted with the reality of having to take up a subject position available to young Coloured men living on the Cape Flats. I learnt from a very early age that if I wanted to be taken seriously as a boy (and later as a man), I would have to abide by the dominant constructions (subject positions) of manhood and masculinity (ie, being physically strong, fearless, and unquestionably heterosexual). These dominant constructs of manhood were not only unreachable for me (as I wasn’t physically strong, fearless, and unquestionably heterosexual), but my involvement in church, especially singing, inadvertently positioned me a “soft”.

My reputation as a joker, troublemaker, rugby player, and academic achiever at school, and my reputation as a youth leader and singer in the church band, caused much internal conflict and at times confusion. It was as if I inhabited two conflicting identities, two versions of myself: one suitable for home/church and the other suitable for school. I tried (and failed) to keep my church/home “persona” separate from my school persona. I was convinced that singing like a girl and attending church as religiously as I did was tantamount to masculine suicide. Boys and young men at my school who did not adhere to dominant scripts of manhood were routinely mocked and bullied. They were almost always called “moffies” (a derogatory Afrikaaps word denoting a same sex attracted man) not necessarily because they were same sex attracted, but because they were soft spoken, effeminate and had female friends with whom they were not romantically involved. On a few occasions I was also called a “moffie” simply because I (with some other church friends) were signing. The boys mocking us would also say that we “sang like girls” (this is to suggest that we had high-pitched voices).

Furthermore, I was actively involved in various NGO’s working with young people, these included SPADES and Love Life. I was a peer educator and later a trainer and facilitator at both these organisations. I also worked for the YMCA, conducting various awareness programmes. The programmes conducted by all these organisations covered similar themes, examples include: safe sex, discouraging gender based violence and sexual harassment, respect and care for humanity and the environment, abstaining from drugs and alcohol, promoting education as a route to economic and social mobility. I was a youth leader in our church and formed part of Y-Impact, a faith-based NGO working with youth. The young people I encountered were often referred to as ‘troubled’ due to their involvement with street gangs, drug abuse, and violence. It was my interest in the different kinds of young people who are branded as troubled (or better yet: moeilikheid) that ultimately informed my decision to pursue a degree in Social Work.

Photo: Me in Grade 1 at Merrydale Primary School, Mitchell's Plain.

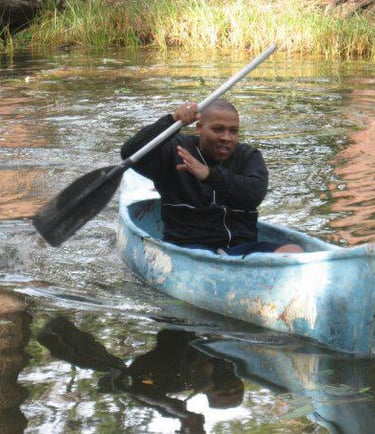

Photo: Me during a team building activity at a Prefect LRC School Camp.

Working with "Trouble"

My involvement in the community and the church, in a way, gave me a firm grounding in what I wanted to do with my life. That was: to contribute to and to advance equality, social justice, and human development. After graduating from university, I was employed by a faith-based NGO working in the southern peninsula of Cape Town. This organisation had a drop in facility providing for the immediate needs of the homeless, such as food and ablution facilities. The centre also boasted an outpatient rehabilitation facility, which I managed. My work at this organisation was mainly to execute social work interventions with “addicts”; provide trauma debriefing/counselling and referral services to members of the public (usually victims of rape and trauma) who came to the facility; and to work with children and youth attending nearby schools – these young people were labelled as “at risk”. Children and youth “at risk” were those who had lost interest in schooling; bunked or had dropped out of school; and any other learner who, according to teachers, had “discipline issues”.

The majority of my clients were between the ages of 15–35. The more I was called to “intervene” with these troublesome young people, the more interested I became in exploring this at a postgraduate level. I was particularly interested in the “trouble” associated with homeless children and youth. I wanted to know more about how they construct trouble, their experience of and exposure to trouble, as well as the trouble they create. I then enrolled for an MPhil degree in Criminal Justice, with a particular focus on children and young people labelled as “at risk” and/or “risky”. For the research component of my master’s degree, I conducted a qualitative study into the lives of young people who lived and worked on the street. Young people who live and work on the street probably best embody academic and public discourses around “troublesome”/ “at-risk”/ “risky” children and youth. However, I approached “trouble” as a disruptive tool rather than as a label denoting some kind of social deviance. I was interested to understand how these young people, in their own words and on their terms, rationalise their actions and behaviours. This work provided me with fascinating insights about the condition of homeless youth, as well as how young people navigated the streets. I learnt about street subcultures, group roles and responsibilities, as well as ways in which boys and girls were policed. I also developed key insights into how these young people (particularly boys) relate to figures of authority (in school and at home) as well as their concerns and aspirations.

Researching "Trouble"

My professional work (and later my academic research) with children and youth is motivated by my belief in the centrality of the client in any intervention. Inspired by the work of social psychologist Carl Rogers, I have adopted a “person-centred” approach in both my social work practice as well as my research with “troublesome” children and youth. Carl Rogers argued that persons possess resources of self-knowledge and self-healing, and that behavioural change and development are possible when therapists create an environment which facilitates such client-centred reflection. This person-centred approach is what underpins my work as a therapist, activist, and scholar. Likewise, my research encourages the voices of young Coloured men who are often marginalised and pathologised in the media as well as in popular discourses. My research endeavours to provide a critical and empathetic account of young men’s experiences growing up in contemporary South Africa. My research illuminates how young men talk about their concerns, desires, pleasures, aspirations, and identifications, as well as shows how they creatively and critically reflect on their lives, their social environments, and their relationships with others.

My research is a platform I use to not only reflect on the complex lives of my participants, but I also turn this focus inwards. In other words, I am alive to my historically produced subjective experiences (of race, gender, sexuality, class, etc) and the kinds of relationships I established with the young Coloured men in my study. My research is a robust engagement with questions about the complexity of gender-power relations in schools, it engages young men as complicit but also resistant to particular kinds of gender regimes, as well as interrogates the social practices that polarise masculinities and femininities in schools. To this end, I engage young Coloured men as active agents who actively construct their identities, albeit in social and material conditions not of their choosing. Moreover, I address young Coloured men as experts about their own lives, who through individual agency engage with, accept, contest, recreate, and conform to dominant forms of masculinity in particular kinds of social and economic contexts. Similarly, whilst not denying the dominant hegemonic ideal concerning compulsory heterosexuality, violence, homophobia, and misogyny that many Coloured young men subscribe to, I disrupt this narrative by showing how the same participants express and embrace emotion, empathy, care, intimacy, and love. This is important to highlight, as the caring and nurturing aspect of Coloured masculinity has received little attention in the literature and popular media. In doing this, my study seeks to contribute to a discourse that appreciates the complexities associated with performing Coloured masculinities, and how that intersects with race, class, sexuality, and age.

Photo: Me in Matric at Portlands High School, Mitchell's Plain.

Photo: Me as a student leader at UCT addressing students before a march to Bremner Building.

Photo: Here I am pictured with my PhD supervisor, Prof. Rob Pattman, at a conference. Prof. Pattman has been a central figure in shaping my thinking, scholarship, and pedagogy. His unwavering belief in me, even when I was seen as radical, profoundly impacted the way I now engage with students. He taught me to look beyond labels and see potential where others might not. Today, I carry that lesson forward, striving to offer my students the same compassion, belief, and guidance he offered me.

Educational Background and Academic Contributions

I hold a Bachelor of Social Work (with Honours) and a Master of Philosophy from the University of Cape Town, and a PhD in Sociology from Stellenbosch University. Shaped by interdisciplinary training at leading research-intensive institutions, my work over the past decade has explored how race, class, and socio-political inequalities affect children and youth in South Africa. More recently, my research and activist efforts have focused on innovative approaches to advancing social justice, particularly in the areas of violence and injury prevention, non-violent conflict resolution, and peace promotion among children and youth within educational settings in Southern Africa.

To this end, I have contributed to several major research projects, including Learning from the Learners (led by Professors Deevia Bhana and Rob Pattman), Engaging South African and Finnish Youth in Non-Violence (led by Professors Jeff Hearn, Tamara Shefer, and Kopano Ratele), and the South African School-Based Violence Study (led by Dr Patrick Burton). My doctoral research, titled Love, Learning, and Identities at New Hope: An Ethnographic Study of How Young Coloured Men Construct and Perform Race, Masculinity, and Sexuality at a Northern Cape High School, examined the complex and often contradictory ways in which youth navigate educational and social life in a rural farming town marked by racial and class divisions. Despite confronting exclusion, discrimination, and marginalisation, the young men I studied demonstrated resilience and agency, illuminating the nuanced realities of post-apartheid South African youth.

My research contributes to contemporary scholarship on youth, resistance, resilience, and networks of care. I have shared my work at numerous national and international conferences, seminars, and colloquia, and it has been well received across both academic and applied contexts. In recognition of its impact, I was awarded the Early Career Researcher Award by the American Men’s Studies Association in 2022 and received a research grant in 2023 from the International Sociological Association’s Research Committee on the Sociology of Education (ISA RC04).

Professional Experience

Lecturer, 01/11/2021 – Present. The University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa.

Lecturer and Project Coordinator, 01/07/2018 – 30 October 2021. The University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

Lecturer, 01/06/2016 – 31/06/2018. The University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa.

Social Work Clinical Supervisor, 01/07/2013 – 30/06/2016. Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa.

OCSAS Manager and Student Support Officer, 01/03/2012 – 30/05/2013. The University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

Social Worker / Programme Manager, 1/02/2011- 28/02/2012. Hope: Cape Town, South Africa.

Professional Membership and Registrations

American Sociological Association (ASA), Member, 2020 – Present.

International Sociological Association (ISA), RC 04 Sociology of Education, Member, 2016 – Present.

South African Sociological Association (SASA), Member, January 2013 – Present.

South African Council for Social Service Professions, Registered Social Worker, 2011 – Present.

National Association of Social Workers, Member, 2011 – Present.